Nodes

This time last week I was halfway through a six hour, round-trip hike to an alpine lake. My partner had taken the week off and we’d climbed high enough to have hit some light snow about an hour ago. Our phones had been without signal for two hours, and we hadn’t seen another soul for three. Suddenly we came across a dank, magical grove filled with the most beautiful mushrooms I have ever seen.

They were straight out of a video game: bigger than my fist with a bulbous, deep scarlet cap and large, knobbled, creamy-white spots. But these toadstools were more realistic and downright wild than Mario’s. It must be the season here on Vancouver Island as there were plenty of them on our hikes – many of which I had never seen before in my life. I suspect that’s because I’m a relative newcomer to the Pacific Northwest, but not all funghi lay in plain sight; many were under logs and hidden in the brackish brush around the trails. You had to pause and peek to see many of them.

It made me wonder: perhaps I’ve been missing out on all kinds of amazing funghi my whole life because I failed to stop and take a closer look?

Mighty

Some things are common knowledge or easy to find. I could leave my apartment right now and find some button mushrooms within ten minutes (humble brag). Sure, they would be at a grocery store, but the point is I know what they look like and I know how to find them.

Other things are almost-impossible to find. Many dedicate their lives to searching for objects, ideas, proofs and results.

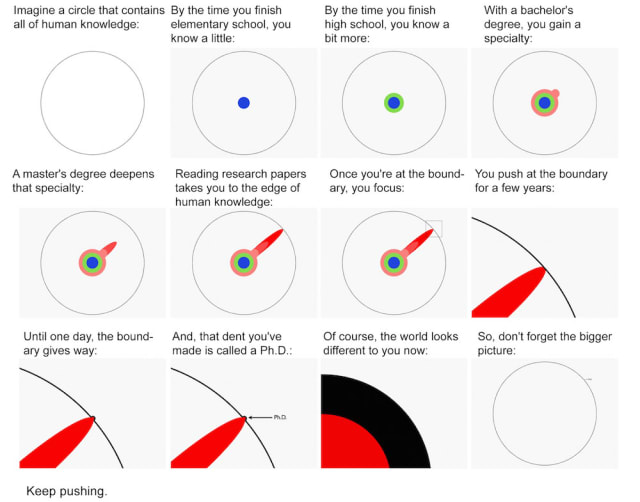

Professor Matt Might of the University of Alabama at Birmingham put together an illustrated guide that provides a broad understanding of what, exactly, people are doing when they work on a Ph.D. or similar. It’s a visualization that has inspired many as they push the limits of human knowledge through academic research.

I first saw Might’s work years ago and think about it often. Researching it again for this edition I found that the story of his family since then has emphasized his “keep pushing” mantra. When their son Bertrand was six months old they discovered he had an “ultra-rare” genetic disease. It was estimated that only 500 other living patients had the disorder.

Re-orienting his work in academia he helped forge connections with other parents of children with the rare disability and expanded the limit of human knowledge to help countless others in the future.

Might’s improbable and inspiring story is the true embodiment of his own motivating rally-cry of “keep pushing.”

The Circle of This Content

I’m the sort of person who finds it hard to enjoy something if it reaches a certain level of popularity. It’s a self-sabotaging tendency to the unique – a fascination to the fringe. That’s not to say I don’t enjoy popular things. I just approach everything with fresh eyes and trepidation, waiting for the switch to be flipped before I become a fan.

In a soft quest to understand why I’m like this I’ve been thinking a lot about the homogeneity of popular culture and how it relates back to knowledge. Take TV: The Ted Lassos and Squid Gamers of 2021 are at the center of a circle of popular culture right now, joining perma-favourites like The Office.

And then there’s the internet. Think of the eternal reposts of the same articles across the web. Popular news sites and aggregators like Reddit are at the center of a maelstrom of content. Everyone has their own neighbourhood they enjoy. Many are satisfied with the center and others will prefer to explore the niche newsletters striving to share something a little different.

Inspired by Might’s “Keep Pushing” circle, we could visualize popular culture at the center with more narrow interests towards the circumference.

World Wood Web

Sometimes culture surprises us and the fringe shifts towards the center. In a rare link between the popular and academic, Ted Lasso name-dropped a Professor of Ecology from the University of British Columbia last week.

You know, we used to believe that trees competed with each other for light. Suzanne Simard’s field work challenged that perception, and we now realize that the forest is a socialist community. Trees work in harmony to share the sunlight.

Prof. Suzanne Simard’s bestselling book, “Finding the Mother Tree” gives a full treatise of her decades of work in the field forest researching and confirming the role of mycorrhizal networks. This is the symbiotic association between green plants and fungus.

By analyzing the DNA in root tips and tracing the movement of molecules through underground conduits, Simard has discovered that fungal threads link nearly every tree in a forest — even trees of different species. Carbon, water, nutrients, alarm signals and hormones can pass from tree to tree through these subterranean circuits.

This symbiotic association is suspected to also be found in “prairies, grasslands, chaparral and Arctic tundra — essentially everywhere there is life on land.”

Together, these symbiotic partners knit Earth’s soils into nearly contiguous living networks of unfathomable scale and complexity.

These quotes are from an article in the New York Times I linked back in source/target ~ #23 – I think you’ll like it.

Would you like chips with that?

In a 2018 research article with the delightful title “Towards Fungal Computer,” Andrew Adamatzky posits a future where networks of mushrooms with the ability to conduct electricity could be used as a form of semiconductor. These networks are known as “mycelia” and are found underground and elsewhere, most notably in rotting tree stumps, like the ones I hiked past last week.

Sourcerers will know that researchers have been looking at the use of protoplasmic slime mold networks, but this novel funghi approach appears to be more flexible. According to Adamatzky, we can “reprogram a geometry and graph-theoretical structure of the mycelium networks and then use electrical activity … to realize computing circuits.”

On first pass it may sound like the author may have consumed a few too many electrifying, magic mushrooms but there are some smart proposed applications of these networks thanks to the incredible capabilities of our fungal friends:

Fungi “possess almost all the senses used by humans” and can sense “light, chemicals, gases, gravity and electric fields”

Likely application domains of fungal devices could be large-scale networks of mycelium which collect and analyze information about environment of soil and, possibly, air and execute some decision-making procedures.

One interest I picked up in the pandemic was monitoring weather and air quality using a little Raspberry Pi sensor made by a company in England. It’s cool/weird to think that some funky fungus network could do the same thing with a spark.

The Graphs for the Trees

I’m inspired by the work of Might, Adamatzky and Simard and reminded how much there is to know and understand of the world around us.

The next time you’re in a forest or woods let your curiosity lead you a little – you never know what networks may be connected under the leaves.

Links

- A Gentle Introduction to Graph Neural Networks

- A traffic paradox demonstrated via springs and ropes

- Using Git Graphs to Visualize Dialogue Systems in Games

- A tool to visualize decentralized social networks

- Drawing graphs in SketchViz

Nodes

You probably heard that Facebook and related properties were offline for most of the day the other week. As a story that had a wider impact than you may expect many were quick to attempt to explain what had happened. This article from Julia Evans gives a great summary from a visualization perspective using one of the jankiest-yet-productive online tools I’ve ever seen – BGPlay. It’s a good reminder that tools don’t have to be beautiful to be helpful. There’s no excuse for lack of discoverability though.

Here’s a neat look at summarizing writing by stripping out everything that isn’t punctuation. With practice, you could likely identify someone’s writing by the punctuation they used, as it highlights their tendency to use particular clauses and phrases. I’d love to take this a step further and find a way to compare changes to writing over time by deriving a graph of typical clause flow.

This article argues that humanity’s collective rush to get satellites into space is a double-edged sword: it’s helping connect remote communities to the internet,

One of the stories that I like to tell is that we had an elder that was excited once we connected his phone to it,” Ashue said. “He was calling people and saying, ‘I’m calling you from my couch. I don’t have to stand outside in the rain,’” because previously “in order for his cell phone to work, he had to go out toward the road.

but robbing indigenous communities and others of the constellations that have guided and inspired for literally thousands and thousands of years.

We’ve talked about the night-sky-as-a-graph in previous editions but I’d never heard of “dark constellations”:

They are shapes in the sky made out of the dark spaces, opposite to Western constellations that make shapes out of the starlight.

With the increase in light pollution due to these reflective objects in space, we can no longer access these dark constellations,” she added. “That means we can no longer monitor our cultural signals that tell us about the seasons or ceremony timing, or even access our knowledge, as much of it is stored in the sky. If we cannot access our skies, we cannot practice our culture.

Similar to “It’s not the notes you play, it’s the notes you don’t play,” perhaps it’s the stars we can’t see that are making the largest impression.

I’m excited to be part of a panel on writing about data visualization next week. It’s part of the VisInPractice satellite for IEEEVIS 2021. I’m in great company with participants from Market Cafe Magazine, Nightingale and Multiple Views: Visualization Research Explained.

More business this week. My talk for B-Sides Vancouver earlier this year is now on YouTube. It’s called Attack of the Graph: Visual Tools for Cyber Analysis and gives a brief coverage of a range of applications of graphs in information security use-cases. There was so much more I’d like to cover in the future but I was thrilled to be part of such a well-organized, domain-specific conference.

I’ll leave you with a melangerie of mushrooms to close this one out. Until next time!