“I’m sorry, Tom Hanks says you have dead eyes. We’re going in a different direction.”

It had been a whirlwind week for Conor Ratliff. He’d flown across the country for one final meeting with the Director of a new HBO show, Band of Brothers. This was unusual, he had been cast as the character John S. Zielinski – surely it was a done deal?

Ratliff has been in numerous popular projects, even mainstream shows like The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel, but the rejection gnawed at him enough to instigate the inevitable: start a podcast. Rather than a bitter character assassination of the “Nicest Man in Hollywood”, Ratliff’s podcast “Dead Eyes” is a twisty, tender look at the the realities of being a jobbing actor in the 21st century.

In episode 31, Ratcliff met the instigator of all this angst for a beautiful conversation. For his part, Tom Hanks barely remembers the sequence of events that lead to Ratcliff being removed from the show. Despite this, Hanks duly takes full responsibility for the decision; providing a measured look at the “billions of tiny decisions” a director has to make, day-to-day.

One example stood out to me: A set designer might ask, "Do you want the red coffee cups or the blue?"An apparent insignificant decision like this one moment, can take on new weight on the day of the shoot when the blue (or red) looks out of place.

And yet, there isn’t enough time to agonize over each of these tiny decisions. Doing so would delay movie production and dilute the production’s vision.

Type II Agonizing

Friends and family tell me I’m not all that great at decision making. Their words echo in my head while I agonize over choices. Even after I make a judgment, it can take a long time to shake off the nagging feeling of potential regret.

While I sometimes resort to flipping a coin, I heard a suggestion recently: faced with two options, always go for the one that’s more difficult. It’s a heuristic but it makes some sort of sad sense! In some twisted way I may be happier making a decision that prompts time and effort than a decision that could ultimately be chalked up to good luck. It builds character.

Another popular piece of advice on decisions comes from Jeff Bezos. Decisions can be classified as either Type I or Type II decisions: those that can be reversed or those that cannot. Type II decisions should be made quickly so more time can be dedicated to Type I decisions that will be set in stone. Sounds reasonable. But what if it’s hard to tell if your decision is in either camp? Back to coffee cups: choosing the red vessels isn’t irreversible, but there is a reversal cost. Like a movie director, if your time is spent with thousands of reversible decisions, how do you pause the maelstrom of mental fatigue that puts you under?

Origin of Saran Wrap

Charles Darwin was an avid diary writer and took lengths to itemize a number of big decisions in his life. Per “The Art of Decision-Making,” Joshua Rothman notes

Darwin was considering proposing to his cousin Emma Wedgwood, but he worried that marriage and children might impede his scientific career. To figure out what to do, he made two lists. “Loss of time,” he wrote on the first. “Perhaps quarreling… Cannot read in the evenings… Anxiety and responsibility. Perhaps my wife won’t like London; then the sentence is banishment and degradation into indolent, idle fool.” On the second, he wrote, “Children (if it Please God). Constant companion (and friend in old age)… Home, & someone to take care of house.” He noted that it was “intolerable to think of spending one’s whole life, like a neuter bee, working, working… Only picture to yourself a nice soft wife on a sofa with good fire and books and music perhaps.”

I find it fascinating that despite writing these thoughts down, there’s no indication of how he decided on, ultimately, marrying Wedgwood.

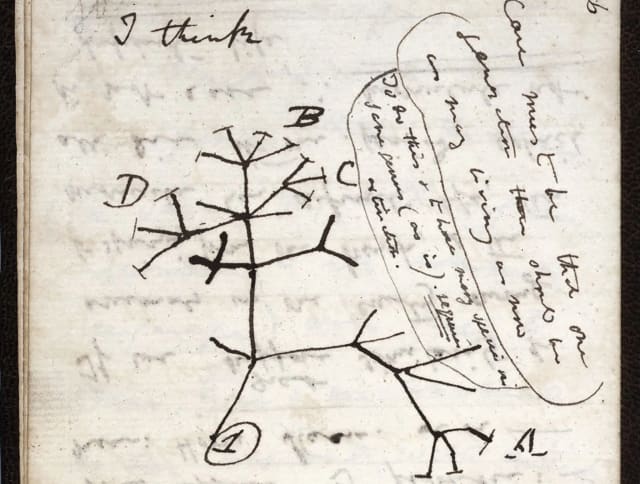

Last week a lost notebook of Darwin’s, last seen in 2000, was dropped off at a University library in Cambridge with an enigmatic message.

Librarian

Happy Easter

X

Encased in plastic wrap, the notebooks contain a variety of thoughts and drawings by Darwin including his iconic “Tree of Life” sketch from 1837. I like to imagine some sort of two column decision list by the person who held these notebooks for 20 years; a deep deliberation on doing the right thing over the risk of punishment.

Micro / Macron / Le Monde

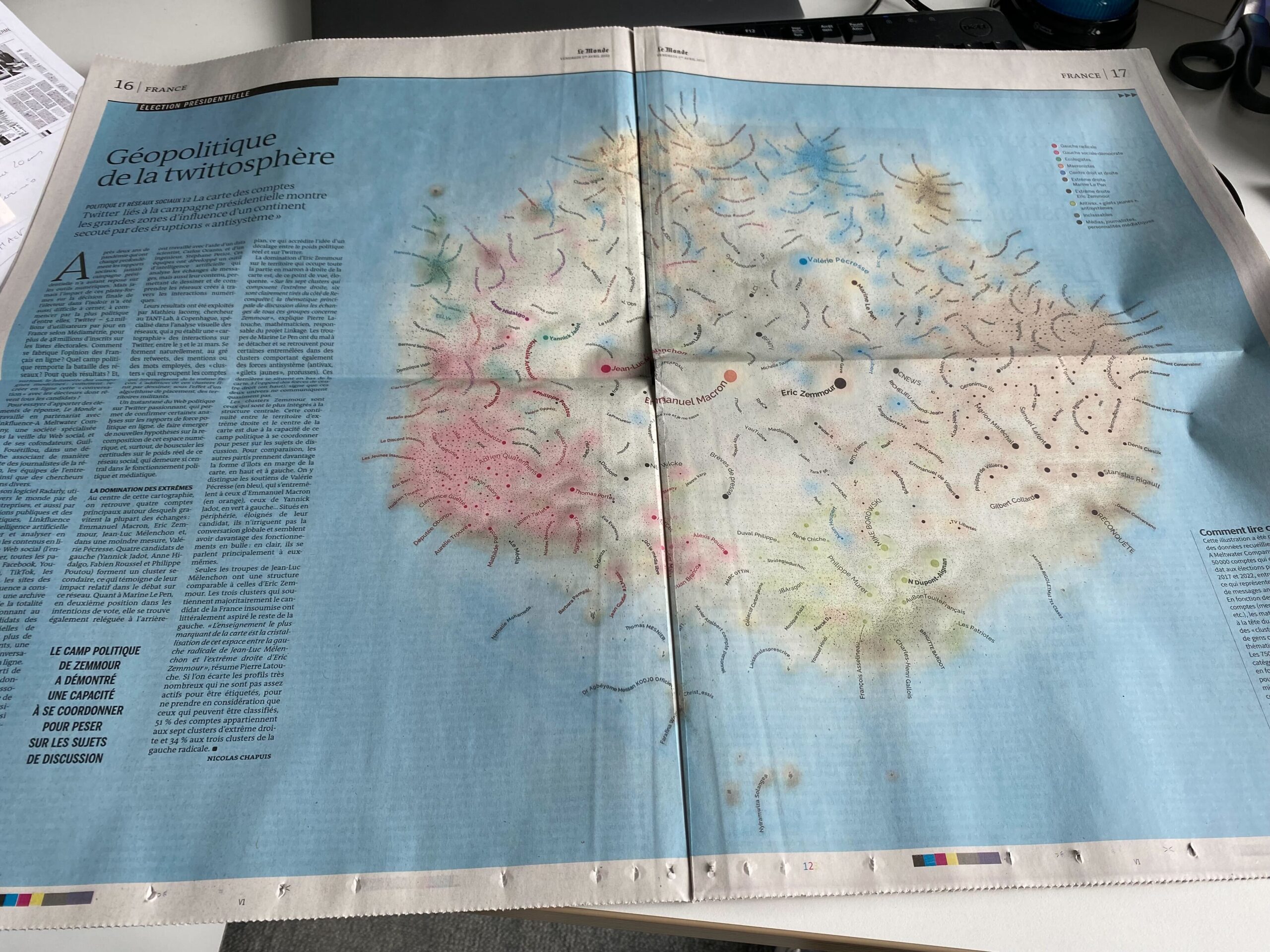

In an article on his blog, Mathieu Jacomy wrote about the thought and attention that went into a large-scale graph visualization project for Le Monde. In it, he mapped out vast swathes of Twitter to plot out discourse surrounding the ongoing French presidential election. But instead of digging into how the visualization was built, he took a magnifying glass to the many thousands of decisions he had to take – the whys that resulted in an eye-catching, rewarding visualization.

A few points were obvious: left- and right-leaning candidates should be on their respective sides of the graph.

A few were political: flags are a bad representation of nationalities, and political allegiances are hard to derive from published or self-identifying sources.

And then there’s the aesthetic and the happy accidents: not showing links between people significantly reduced the clutter in the network, and certain shades of color matched the paper’s style guide for political content.

Practical decisions that intersected with aesthetic ones were another happy coincidence. Through curvy names snaking across the landscape of political discussions, Jacomy is able to avoid overlaps whilst providing an overall effect that’s pleasing to the eye.

In typesetting there’s the concept of rivers: unless a page is calibrated just right there will be gaps across the lines and paragraphs that draw attention from the main event. Jacomy notes that writing text from left to right can result in undesirable troughs of ink that can create a misleading effect when layered on top of the network.

Work Logging Rhythm

Many things jump out from Jacomy’s process. For a start, there’s a healthy selection of comparison screenshots. As with any design process, I find a work log is a healthy way to keep track of a project. Liberally collecting outputs of one’s process along the way makes it easy to justify decisions and provides rich fodder for fantastic "behind the scenes” blogs such as Jacomy’s.

Feedback loops are extremely important to the process. These are the steps and time required to see the results of a change in your work, for example the time taken to fetch data from a database, transform it and run a network layout. These steps could take many minutes resulting in distraction and delay. Tighter feedback loops give you the opportunity to make so many more decisions. A work log is a perfect complement to a tight feedback loop: a log of your progress and why certain decisions were made.

Of course, building compelling and insightful data visualizations isn’t about making the “right” decision - it can sometimes simply be making “any” decision at all. Perfection is the enemy of finished. Embracing the millions of micro decisions made in a project is embracing the fact that your work may never be as good as you hope or expect. By honing this ability to make decisions you’re also building your instinct, which will compound over time.

T.Hanks for the coffee

There’s an interesting asymmetry to celebrity interactions. For a so-called “normal” person, meeting someone famous is noteworthy, perhaps even life-defining. But for the celebrity, these encounters are extremely commonplace and fatiguing.

When discussing the infamous dismissal, Tom Hanks recounts his coffee cup decision by way of an example, but he’s quick to avoid diminishing such a life-defining moment for Connor Ratcliff to that of an inanimate set-piece.

As he insists, “You are not a coffee cup.”

But in that moment, on that day, Connor Ratcliff was a coffee cup; one caught up in a mass of decisions Hanks had to make to achieve his goal of producing a hit TV show.

When making decisions on the presentation of data we don’t usually come face-to-face with the people represented and connected. Yet, we owe it to them to acknowledge and document decisions that are made in their name. We won’t always get it right but with time we can calibrate our process to understand the true impact of our choices.